Ch003 - Choose your own Adventure

Choose your own Adventure

There are different ways you can use this book to learn to make your own games. Normally books encourage you to start at the beginning and keep reading until you get to the end but this book isn’t (just) like that. The reason is that different people learn how to code and make games in different ways. Also different people have different inspirations that keep them interested and motivated.

This is also true of the way that people play games. There’s a well known model of different play style types by Richard Bartle. This model, which was based on observing and analyzing the behaviors people playing together in a multi-user game, holds that there are four different kinds of play style interests, each of which is given a descriptive name: Griefers, Achievers, Explorers, and Socializers.1

- Griefers: interfere with the functioning of the game world or the play experience of other players

- Achievers: accumulate status tokens by beating the rules-based challenges of the game world

- Explorers: discover the systems governing the operation of the game world

- Socializers: form relationships with other players by telling stories within the game world

Different kinds of games suit different play styles. One of the notable successes of recent years have been open world games that allow you to choose how you play the game. If you want to stick to the main missions you can follow guidance to do that but if you just want to explore or be social or mess around you have the chance to to do that too.

In the same way there are different styles of making games. I’m proposing the following;

- Social makers: form relationships with other game makers and players by finding out more about their work and telling stories in their game

- Planners: like to study to get a full knowledge of the tools and what is possible before they build up their game step-by-step

- Magpie makers: like trying out lots of different things and happy to borrow code, images and sound from anywhere for quick results

- Glitchers: mess around with the code trying to see if they can break it interesting ways and cause a bit of havoc

Open World vs On Rails Learning

A lot of learning and guides suit the planners of this world. They start with a blank canvas and allows you build up your game step by step explaining just about every line of code that you add. This book does just that in the following handful of chapters, they take a structured approach to getting to a minimal platform game and give details of coding concepts (objects, functions, variables, loops and conditionals) in a logical order using concrete examples from our emerging game. This approach is called building up code “From Scratch”.

This book aims to support learners who like a more “Open World” approach to learning. To do this the later sections of this book take a different approach to helping you make games. You are encouraged to various different game features in what ever order you like. The chapters are much shorter and designed to be self-contained. Almost like little side or social missions that you get in great open world games. If you like experimenting you can skip the next set of chapters and user the starting Grid Game Template2 as your jumping off point. You can Remix this game to add in new features and looks right away. If you have been following this book you would have done that in the first chapter.

But to help get an overview of what’s there let’s look in a bit more depth about what makes a good game.

What makes up a Game?

We play them all the time but did you ever ask - What exactly is a game? How is it different from just playing around? The Institute of play list key components that make up a game, be it video or non-digital game. They are as follows.

- Goal: The overall goal of the game, what do you have to do to win

- Parts: What parts make up the mechanisms of playing, this could be physical, like dice or cards, or digital like our enemies, player and other hazards

- Rules: Relationships that define what a player can and cannot do in the game. If…then…or you may…you may not… are good sentence starters for rule making

- Challenge: Obstacles might you put in the player’s way to make reaching the goal fun and interesting

- Space: Where the game take place and how that space affects the game

- Mechanics: The core actions or moves does the player has to do to power the play of the game

The Institute of Play encourage you to think about these different elements of a game to allow you to start to make your own game or to start modding or remxing an existing game. Modding is modifying a game that already exists.

Our own Framework for Game Elements

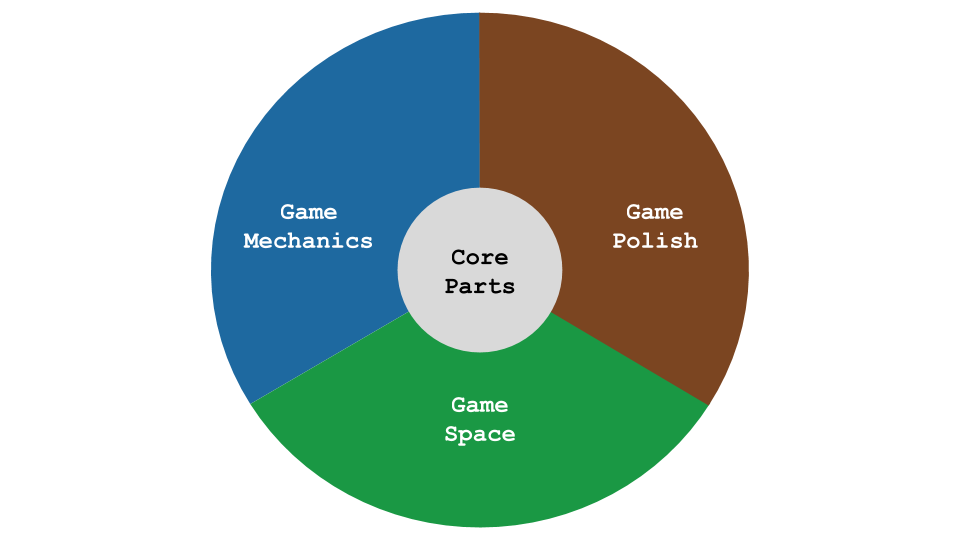

The above framework is great for a deep analysis of how the different parts of your game interact. Frameworks can be great to help us map our journeys. To help us do that we have a simplified framework which has evolved looking at the different requests that our learners make to add different elements to games.

This framework consists of Core Parts, Game Mechanics, Game Space and Game Polish. Core parts of our game are similar, this involves the individual elements of the game and their attributes, we may add more enemies for example. Game Mechanics in our definitions is about what you do in the game. Where game parts are nouns and mechanics are verbs. So for our platform core mechanics would be jumping and collecting. However some of our mechanics are a bit more like more like extra challenges or rules, like adding a timer. So this is a fairly wide definition of game mechanic in line with broader definition from Sicart3. Game Space includes the design or new levels and anything that opens up space like keys and doors or scrolling screens.

Game Polish or game aesthetics is a dimension identified as one of the four pillars of game design by game theorist Jesse Schell 4. He makes a distinction between the mechanics of the game, system elements that effect the core functioning of how the players interact with the game and that of the game aesthetics. Aesthetics here are the wrapping of the game, not core to how it works but which have an effect of the game on the emotions and state of mind of the player. For example the flavour of the graphics and the sound design.

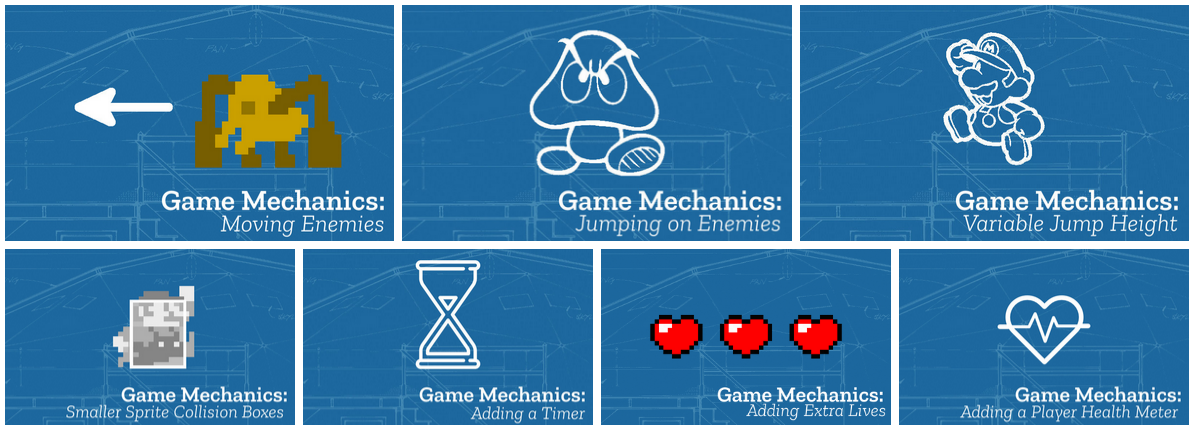

Adding / Changing Game Mechanics

What game mechanics can we add to our platform game? You can choose from some of the following.

- Adding Moving Enemies: make it harder for your players to get past your enemies

- Jumping on Enemies: to make them disappear, a mechanic made famous by Mario

- Variable Jumping Heights: if you press down longer you jump higher

- Smaller Collision Boxes: If your game is too hard, you can set smaller hit boxes, lots of platform games do this

- Add a Countdown timer: this can increase the challenge of your levels, players must complete them before time runs out

- Extra Lives: if you touch a hazard you lose a life and have to restart with one less life (to come)

- Adding Player Health: if you touch a hazard you lose health instead of losing a life

Adding Game Polish

Elements of Polish are often not core to how the game works as a system but the are key to how our player reacts to our game. The following changes can help.

- Add your own Sound Effects: swapping out existing sounds and adding new ones for example when you jump

- Add Animation to your character: make them look like they are running or jumping

- Add Soundtrack Music: have some music on a loop when game play is happening

- Animate Character when Zapped: here an animation is played when a player or character gets zapped

- Screen Shake: mimicking a shaking screen to create a dramatic ending

- Explosion on Dying: use particles to mimic an explosion when a character dies

Changing Game Space

Here are some things you can change around the way you game uses space or give the player the feeling of exploring space.

- Add your own Background: you can create your own pixel art or drawn background to add to the game

- Add Game Over Screen: let your player know when they have failed!

- Scaling our Game and Sprites: this may be for aesthetic effect or could affect game mechanics too

- Adding Levels: This can increase the challenge of our game greatly

- Extending the Game Size: if you want your game to scroll as your player moves, this is how!

- Keys and Doors: collect keys to open previously closed doors can add as sense of adventure to your platformer

- Create a Cut / Opening Scene: A great way to introduce rules, info about your game or a story

- Adding Levels with Json: a neater way to create your levels and a way to find out more about data structures.

Go On Choose your own Adventure

So go on and choose how you want to progress. As described you can start from scratch and build up your code bit by by bit so you really understand how each part works. You can do this by following the next chapters starting with Building a World.

Alternatively, if you like to just jump in, you can keep changing the Grid Game code, adding in graphics and tinkering around by adding things from the examples just listed above. [This page on Glitch also lists the code examples.5](http://ggc-examples.glitch.me/)

Meeting yourself in the middle

Another way to do this is to try both approaches at the same time. In this way you get all of the fun of adding in new exciting game elements to a working game but can back this up by following a logical structure as well. To help you make a connection between the From Scratch approach and the tinkering with the Grid Game approach you can dive into the chapter called Understanding our Game Structure. If may want to read that when altering the Grid Game if you get confused when making larger changes.

- https://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/134842/personality_and_play_styles_a_.php

- https://grid-game-template.glitch.me/

- http://gamestudies.org/0802/articles/sicart

- Here’s the book https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/the-art-of/9781466598645/ and here’s a summary http://www.gamification.co/2013/09/24/adapt-gamification-designs-with-jesse-schells-four-pillars/

- http://ggc-examples.glitch.me/